Earlier this year I got an article published in Acta Borealia.

The paper, The Sami cooperative herding group: the siida system from past to present, is open access.

I usually publish a short summary on this blog, but recently I’ve been learning to analyze text using Python so I thought I should try to leverage Python to help me summarize my own paper.

The result? Have a look (I’ve only removed citations and reorganized the sentences for flow):

Background

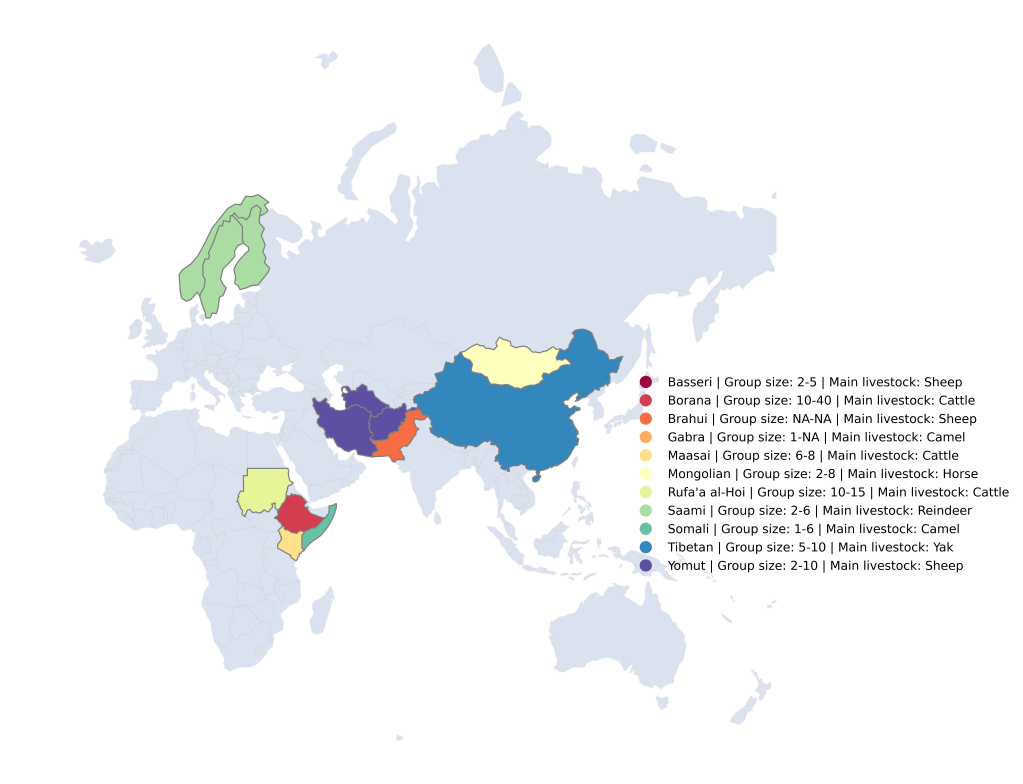

The Sami – both pastoralists and hunters – in Norway had a larger unit than the family, i.e., the siida.

History

Historically, it has been characterized as a relatively small group based on kinship.

The siida could refer to both the territory, its resources and the people that use it.

The core institutions are the baiki (household) and the siida (band).

Names of siidas were, in other words, local.

Moreover, it was informally led by a wealthy and skillful person whose authority was primarily related to herding.

One of these groups’ critical aspects is that they are dynamic: composition and size change according to the season, and members are free to join and leave groups as they see fit.

Results

Only two herders reported to have changed summer and winter siida since 2000.

Furthermore, while the siida continues to be family-based, leadership is becoming more formal.

Nevertheless, decision-making continues to be influenced by concerns of equality.

Code

The code is shown below. Lacks a bit in comments, but should work for documents. I’ve load the text used from a docx file.

Imports

import numpy as np

import os

import sys

import nltk

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

import re

import textacy # have installed spacy==3.0 and textacy==0.11

import textacy.preprocessing as tprep

import docx

import networkx as nx

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer

import nltk

import os

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

stop_words = nltk.corpus.stopwords.words('english')

wtk = nltk.tokenize.RegexpTokenizer(r'\w+')

wnl = nltk.stem.wordnet.WordNetLemmatizer()

Loading file

doc = docx.Document('your_filename.docx')

Functions for processing and summarizing text

def extract_text_doc(doc):

paras = [p.text for p in doc.paragraphs if p.text]

revised_paras = [p for p in paras if len(p.split('.')) >1]

text = " ".join(revised_paras)

return text

def normalize_document(paper):

'''

Tokenize ++

'''

paper = paper.lower()

paper_tokens = [token.strip() for token in wtk.tokenize(paper)]

paper_tokens = [wnl.lemmatize(token) for token in paper_tokens if not token.isnumeric()]

paper_tokens = [token for token in paper_tokens if len(token) >2]

paper_tokens = [token for token in paper_tokens if token not in stop_words]

doc = ' '.join(paper_tokens)

return doc

def normalize(text):

'''

Normalizes text, string as input, returns normalized string

'''

text = tprep.normalize.hyphenated_words(text)

text = tprep.normalize.quotation_marks(text)

text = tprep.normalize.unicode(text)

text = tprep.remove.accents(text)

return text

def text_rank_summarizer(norm_sentences, original_sentences, num_sent):

if len(sentences) < num_sent:

num_sent -=1

else:

num_sent=num_sent

tv_p = TfidfVectorizer(min_df=1, max_df=1, ngram_range=(1,1), use_idf=True)

dt_matrix = tv_p.fit_transform(norm_sentences)

dt_matrix = dt_matrix.toarray()

vocab = tv_p.get_feature_names()

td_matrix = dt_matrix.T

similarity_matrix = np.matmul(dt_matrix, dt_matrix.T)

similarity_graph = nx.from_numpy_array(similarity_matrix)

scores = nx.pagerank(similarity_graph)

ranked_sentences = sorted(((score,index) for index, score in scores.items()))

top_sentence_indices = [ranked_sentences[index][1] for index in range(num_sent)]

top_sentence_indices.sort()

summary = "\n".join(np.array(original_sentences)[top_sentence_indices])

return summary

Processing text

normalize_corpus = np.vectorize(normalize_document)

text = extract_text_doc(doc)

text1 = normalize(text)

sentences = nltk.sent_tokenize(text1)

norm_sentences = normalize_corpus(sentences)

summary = text_rank_summarizer(norm_sentences, sentences, 10)

print(summary)

Historically, it has been characterized as a relatively small group based on kinship.

Moreover, it was informally led by a wealthy and skilful person whose authority was primarily related to herding.

Only two herders reported to have changed summer and winter siida since 2000.

Furthermore, while the siida continues to be family-based, leadership is becoming more formal.

Nevertheless, decision-making continues to be influenced by concerns of equality.

One of these groups' critical aspects is that they are dynamic: composition and size changes according to the season, and members are free to join and leave groups as they see fit.

Lowie (1945) writes that the Sami – both pastoralists and hunters – in Norway had a larger unit than the family, i.e., the siida.

Names of siidas were, in other words, local.

The siida could refer to both the territory, its resources and the people that use it (see also Riseth 2000, 120).

The core institutions are the baiki (household) and the siida (band).

For more options and better ways of summarizing text, check out https://pypi.org/project/sumy/ with its many summarizer classes. For example, TextRankSummarizer is similar (but way better) than the approach taken here.

But similarly, it conceptualizes the relationship between sentences as a graph: each sentence is considered as vertex and each vertex is linked to the other vertex. But, rather than using PageRank from networkx for similarity, it uses Jaccard Similarity.