Just got a paper published in Humanities & Social Sciences Communications.

The paper is open accessed and can be found here.

Using governmental statistics from 2001 to 2018 on reindeer herding in Norway, this paper investigates long term wealth differentials in the reindeer husbandry in Norway.

Noteworthy, the data do not represent a sample of reindeer herders but encompass the entire population of licensed reindeer herders in Norway

The paper argues against a dominant view that livestock, as the primary source of wealth, limits the development of inequalities, making pastoralism unable to support complex or hierarchical organisations (see also this page).

Main results

- From 2001 to 2018, livestock inequality, measured by the Gini coefficient, decreased nationally and regionally.

- Cumulative wealth distribution follows a similar pattern: the proportion owned by the wealthy decreased from 2001 to 2018, whereas the proportion owned by the poor increased.

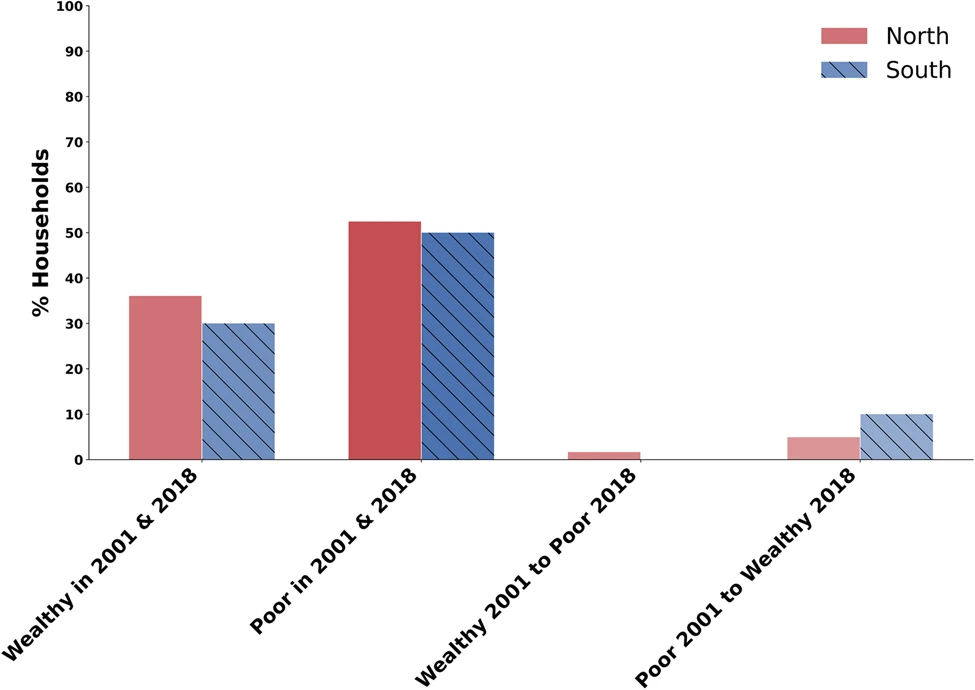

- Rank differences persist with minor changes, especially among the poor; around 50% of households ranked as poor in 2001 continued to be so in 2018.

- Being wealthy or poor differed between regions. For example, households classified as poor in the South had, on average, larger herds than those in the North. Furthermore, compared to the South, wealthy households in the North had, on average, substantially more reindeer while at the same time experiencing much more variation in reindeer numbers

In sum, there is nothing apparent in pastoral adaptation, with livestock as the main base of wealth that levels wealth inequalities and limits social differentiation.

You can read the full paper here.

Annoyingly, the journal cropped one of the figures in the pdf version of the paper so that relevant information is missing. So, Fig.7 should be viewed online until this is corrected (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41599-023-02316-3/figures/7).

But, while we looked at the wealthy and poor, another way to look at wealth differentials is to look at how the poor are doing relative to the middle class, i.e. the 50/10 ratio.

In effect, we can compar the median reindeer number (the number of a herder right in the middle of the distribution) with the tenth-percentile reindeer number (the number of someone near the bottom of the income distribution).

If the 50/10 ratio shrinks it means that poorer households are catching up with the ‘middle-class’ off.

While not addressed in the paper, here is a figure showing that the poor are catching up to the middle-class, especially in recent years.