I’ve just got a paper accepted in Land Use Policy about nomadic pastoralists in Tibet and hunting. As we all know, space is limited in scientific journals, so here is additional text as well as pictures.

A a free copy of the article, made available until April 7, 2016, can be found here.

Hunting has been a subsidiary occupation for the nomads in most of Tibet for a long time. Ekvall (1968:53) writes:

[T]he nomads are enthusiastic hunters. They carry firearms at all times; the demands of pasturing takes them close to the haunts of the herbivores of the higher country; they hunt beasts of prey in order to protect their herds, and they are accustomed to taking life for meat and skin.

As for the nomads in the Aru Basin, they relied on hunting as a supplementary way of making a living, primarily because they were poor, and the opportunity to hunt could be a matter of life and death.

As one nomad said:

When I was young we had no choice but to hunt, if I didn’t hunt my family would starve and maybe die.

And:

When my children were young they had to wear clothes made out of skins from wildlife. I was so poor that I couldn’t afford to make clothes out of sheep and goat skins.

The nomads hunted predators such as bears, snow leopards and wolves because they prey on livestock, while herbivores were hunted because they provided the nomads with a secondary source of meat, skins and furs.

Wildlife in the Aru Basin

The Chiru

The chiru is considered endangered both internationally, and by the national authorities.

The Wild Yak

Estimates of the total number of wild yaks vary dramatically, from 500, to 20 000-40 000.

The Blue Sheep

The blue sheep, a medium sized bovid intermediate to Capra and Ovis but probably more closely related to Capra, is endemic to the Tibetan Plateau.

The Tibetan Gazelle

Tibetan gazelle prefers open landscapes, plains, hills, and even mountains where they may be found in broad valleys and on ridges at high elevations if the terrain is not precipitous.

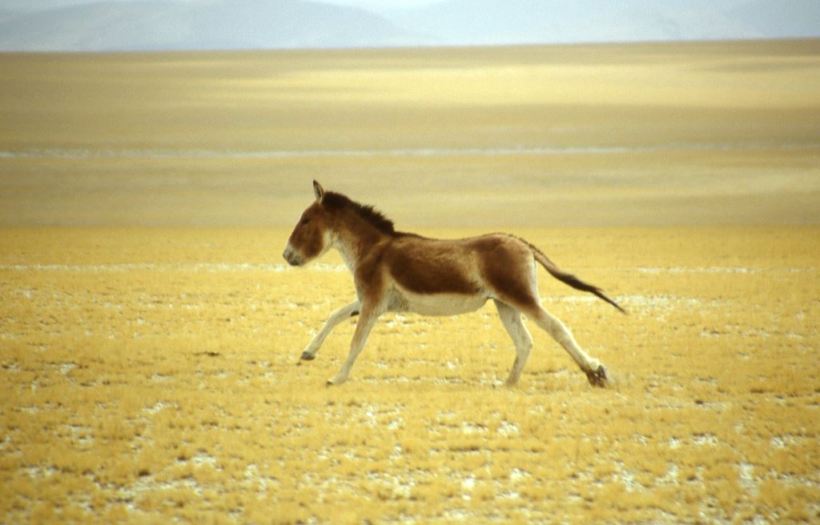

The Kiang

The Predators

The relatively common large predators present include wolf (Canis lupus), snow leopard (Unica unica), brown bear (Ursus arctos), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), sand fox (Vulpes ferrilata), and lynx (Lynx lynx).

Hunting techniques

The Goktse (khog-rtse)

The Aru nomads used a leg-hold trap, called Goktse, to catch antelopes, gazelles, blue sheep and kiangs.

Since animals have different size of legs, the traps were made in different sizes, for wild assess the ring had to be made much bigger while for gazelles it was smaller.

The ponda (bod-mda’)

The Tibetan rifle is not very efficient: if a nomad came across a herd of chirus he would only be able to kill one animal.

After the first shot, all the remaining animals would flee and would be long gone before he had time to reload, since reloading usually takes about 3-5 minutes.

The rifle was the only weapon used for hunting wild yaks, which was not without danger. If they failed to kill the yak with the first shot, the yak would either run away or attack before they could reload.

Wild yaks have been known to kill people because it survived the first shot. One nomad, for example, said that he found a couple of bullets inside a wild yak that he had killed.

The tseka (dzaekha)

The tseka, or funnel trap, was used only to hunt chirus.

They are directed at the antelope’s migration patterns (the females migrate north in May to give birth).

The tsekas were used mainly during winter, except for the ones that were directed towards the female birth migration route in May.

The various wildlife species were also hunted in different seasons, with blue sheep and gazelle only hunted during February, chiru of both sexes hunted in winter and male chiru primarily during summer after the females have migrated north.

The kiang was hunted throughout the winter, even though it was not a preferred target for hunting.

Why hunt?

The nomads primarily hunted the chiru to get extra meat, but also to trade the skins with people from Ladakh in India.

The skins from the chiru were traded because of its very fine fur (shatoosh), a type of wool much finer than cashmere.

According to Schaller (1998) skins from the chiru have been traded from Ladakh to Kashmir for a very long time. In Kashmir, the fine shatoosh wool was woven into high quality shawls, a popular bridal gift for the Indian elite.

They also hunted wild yaks, from which they used the meat and made shoes of the skins. Blue sheep, Kiang and Tibetan gazelle were mainly hunted for meat. Some people also used the skins from blue sheep to decorate their dresses, and some monks bought the skins because they made good material for making drums.

Hunting gave the Aru nomads an opportunity to get meat without cutting into their capital (i.e. animal). As such hunting was an effective way for them to diversify their subsistence base and reduce the risk of falling below a minimum subsistence level.

On the other hand, hunting was also a means of reducing the effect of disasters, in that when livestock was lost due to e.g. a blizzard, they could compensate for this by hunting, and avoid cutting into the capital.

Ban on hunting

During the late 1980’s and the beginning of the 1990’s the popularity of shatoosh wool increased both in India and Europe.

In 1995 the New York store Bergdorf Goodman ran this ad. for shatoosh:

The source of the wool is the mountain Ibex goat of Tibet. After the arduous Himalayan winter is over, the Ibex sheds its down undercoat by scratching itself against low trees and bushes… A difficult process then commences as local shepherds, called Boudhs, from the region of Changtang, Tibet, then climb into the mountains during the three spring months to search for and collect this matted hair (From Schaller 1998:300)

Most of the facts in this quote are wrong, and the international trade of shatoosh has been illegal since 1979 when the chiru was put on the CITES list.

In the early 1990’s prices increased: prior to 1990 a skin could be sold for RMB 60-70, in the early 1990 it had increased to 400. This was primarily due due to increased foreign demand.

The motivation for hunting the chiru changed from mainly being a means of diversifying subsistence risks, to a more “capitalistic” motivation: selling skins could give the nomads a means of making money superseding anything they could dream of making through selling products from their livestock alone.

In the early 1990’s some of the nomads also bought modern rifles. Hunting traditionally, an individual hunter could typically kill around 20-30 animals per year: with the help of modern rifles the take could easily increase to over a 100.

Soon after the chiru provided the nomads with an increased cash flow, a ban was declared on all hunting, since the number of wildlife had decreased dramatically.

The Aru nomads now experienced a decrease in living standard, and several emphatically stated that their livestock did not produce enough milk, wool or meat to sustain them throughout the year.

Also, the ban has resulted in some resentment toward wildlife, and then especially toward the chiru. While hunting gave the Aru nomads a feeling of getting something back from the presence of wildlife, the ban has resulted in the view that wildlife competes with their livestock for forage.

Several nomads stated that they did not believe that life for both humans and chiru is possible in the basin, e.g.:

Whenever we move to summer grazing, the tso [chiru] moves to our winter pasture and eats up all of the grass. When we then come back in winter, there is almost no grass left for our animals.